The Yakama Nation has inhabited the lands in the eastern shadows of the Cascade mountain range since time immemorial. Comprised of 14 Tribes and Bands, the Yakama Nation became a federally recognized tribe when tribal leaders signed a Treaty with the United States government in Walla Walla, Washington in June of 1855.

This treaty ceded much of the traditional territories of the Yakama people to the US Government, but secured 1.3 million acres for the Yakama Reservation, and retained access to resources for the “exclusive use and benefit” of the Yakama people

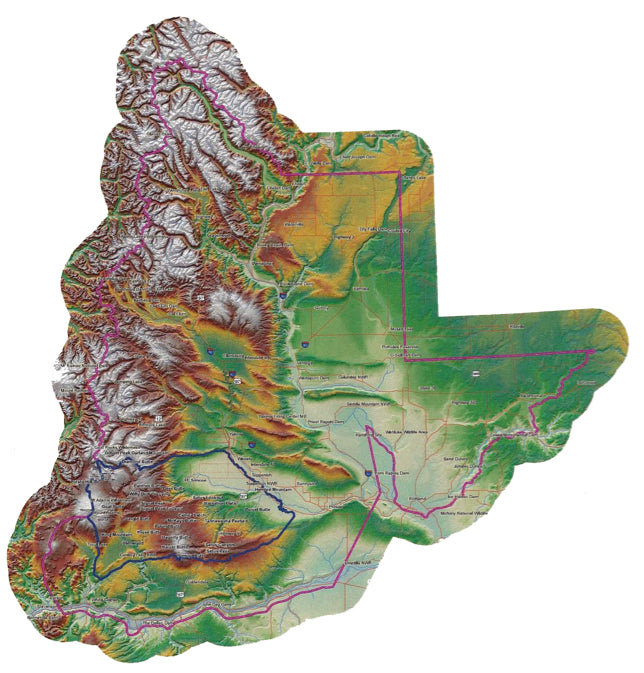

Yakama Nation Ceded Area

Yakama Nation Reservation

After several decades of skirmishes, ultimately culminating with the Yakima War, the majority of the Yakama leaders and their people took up residence within the boundaries of the reservation. However, it did not take long for unfavorable land policies to begin eroding the treaty terms agreed to during the sessions in Walla Walla. There were many detrimental policies enacted during this time, but the most impactful was the Dawes Act of 1887.

The Act facilitated assimilation. The intention was that tribal people would assimilate to a more "Euro-Americanized" lifestyle as the government allotted the reservations and the tribes adapted to subsistence farming. The indigenous communities held specific ideologies pertaining to tribal land, and in contrast to most of their non-native counterparts, they did not see the land from an economic standpoint.

The Allotment Act created a checkerboard pattern of land ownership across Native communities. For the Yakama people, lands were largely broken in to 80-acre parcels. These parcels were then easier to organize and put into agriculture. However, this push for agriculture required one vital ingredient: water. Thus began the formation of the Wapato Irrigation Project.

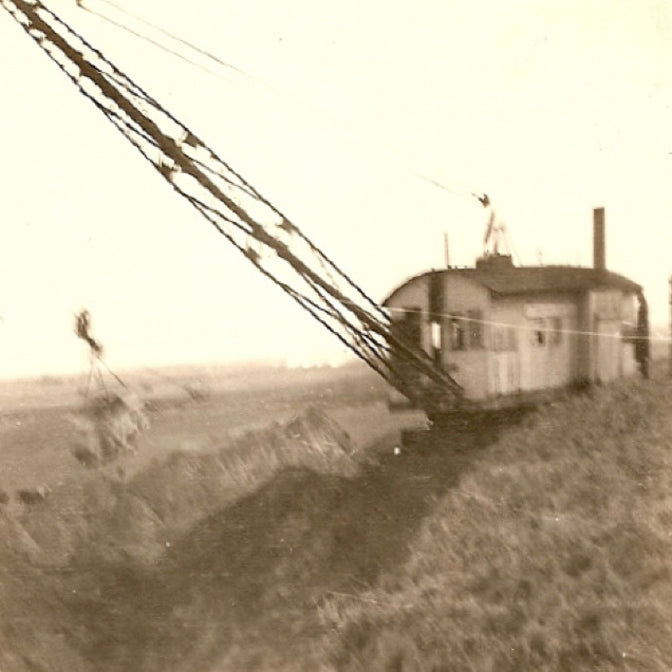

The Wapato Irrigation Project, (WIP), was initiated by the federal government in the early 20th century, and the primary objective was to establish an irrigation delivery system to the lands within the Yakama Reservation. The WIP is one of the oldest and is the largest tribal irrigation project in the United States. Currently, WIP is a federally owned project, operated by the Bureau of Indian Affairs, with assistance from Yakama Nation Engineering staff. The WIP diverts water directly from the Yakima River near the northern reservation boundary and delivers several hundred thousand acre-feet of water to about 150,000 acres of irrigated agricultural land on the reservation.

This water is utilized by a wide variety of diverse agricultural crops. The Yakima Valley, which includes the majority of the Yakama Nation’s agricultural lands, is among National and Washington state leaders in agricultural production. And while the Yakama reservation lands have largely been highly productive for their producers, the Yakama people have not been active participants in many of the agricultural practices within the reservation boundaries. After the Allotment Act, most of the efforts to assist tribal members become successful farmers and ranchers failed. This was due in large part to tribal member’s inability to use their land allotments, which are still held in trust by the United States government, as collateral for loans. This greatly limited the capacity and access of tribal farmers, and many abandoned their fledgling farms. Many tribal members opted to instead take lease payments through the Department of the Interior, from non-native farmers who quickly took those over the development and management of those lands. This soon became the extent of how most tribal members participated in agriculture across the reservation.

And while most of the farming activities on the reservation were owned and operated by non-natives, the Yakama people were the primary source of the labor force for most of the early farms. Generations of Yakama people worked picking crops like hops, tree fruit, corn, and potatoes. However, most Yakama people moved away from working in the crops, which were largely being worked by a growing migrant work force.

Some tribal families did retain their initial livestock herds and developed successful small and mid-sized cattle and horse ranches. These families grew forage crops for their herds, and managed grazing on pasture and rangelands. For most, this was the most successful and accessible way to participate in agriculture on the reservation.

Take a trip out to the farm and experience where the produce on your table is grown!